Among countless literary awards and fellowships, best-selling author Luis J. Rodriguez received an “Unsung Heroes of Compassion” Award, presented by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. His first non-fiction book ALWAYS RUNNING, a first-hand account of gangbanging in East L.A., is used in classrooms throughout California, despite the fact that the American Library Association in 1999 called it one of the 100 most censored books in the United States. In the 1960s, he joined his first street gang at the age of 11 in San Gabriel Valley. He dropped out of high school at age 15 and was also kicked out of his home and became homeless. Under strict conditions set forth by his mother, he was allowed to return home, but had to live in the family’s garage, which had no running water or heat using a can to urinate in.

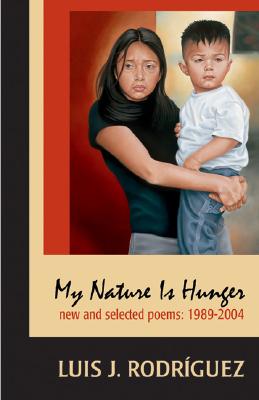

At the same time, Luis became politically involved in the Chicano Movement and was part of the infamous walkouts staged by students demanding equality in education. Luis efforts in community organizing were recognized especially when at age 18 he faced a six-year prison sentence and letters of support were written on his behalf. It was then that he made the choice to dedicate his life to serving the public on behalf of the Mexican American people. His first book of poetry POEMS ACROSS THE PAVEMENT was published in 1989 at the age of 35. Now with fourteen published books in memoir, fiction, nonfiction, children’s literature, and poetry, Luis has a new highly anticipated book called IT CALLS YOU BACK (Simon & Schuster) to be released October 2011. In a recent interview with Reader’s Services’ Elvira Carrizal-Dukes, Luis Rodriguez shared insights about his personal experiences, his previous work, and his new upcoming book.

ELVIRA: What’s the challenge of still relating to your former life and all the things that inspired your first books once you gain notoriety?

LUIS: I have a new book, the sequel to “Always Running.” Its title is “It Calls You Back: An Odyssey Through Love, Addiction, Revolutions, and Healing.” This explains that the rages, addictions, sometimes crimes, do call you back. It’s often a life-long struggle. My new book details the failures, and some successes, I’ve had in dealing with this (it comes out in October). Also because I have four kids and four grandkids, I worry about them. My oldest son got caught up in the gang world and just finished doing a total of 15 years in prison. So this is a constant. The notoriety can get in the way unless I learn to balance this. I do this by focusing on family, my community, the vitality of the arts.

ELVIRA: What influenced you to write your first book and/or how/when did you discover that you were a writer?

LUIS: I began writing as a teenager, in jail, juvenile hall, in the garage room I stayed at after age 15. However, Always Running came about because my son Ramiro, at age 15, joined a gang. I already had written a version of this book and had two books of poetry already published, so in 1992 I worked hard to get Always Running written and published by 1993.

ELVIRA: Do you prefer writing fiction or non-fiction? Why?

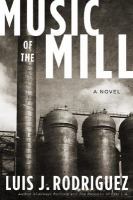

LUIS: I do more non-fiction writing. I have two memoirs, another nonfiction book, and I do lots of essays, journalism, poetry, and reporting. But I love the fiction. As you know I have a novel, a short story collection, and two children’s books. It’s more challenging to write fiction, but I’d like to do more of these. I don’t really prefer one over the other.

ELVIRA: In 1970, at age 16 you were thrown in jail for being involved in the Chicano Moratorium (a Chicano anti-Vietnam War movement). Even though you were a juvenile, you were put in a jail cell next to convicted murderer Charles Manson. Can you discuss the dichotomy of that?

LUIS: Sheriff’s deputies not only put me in an adult jail as a juvenile, they also threatened to place murder charges on me for the three people killed during the East LA riot.

It was wrong, but this happens. Of course, they really couldn’t charge me for murder, but the damage had been done: I was almost killed and I learned to deal with the worse aspects of jail experience in a short time.

I also learned something–if my throat had been cut, like the two murderers in my cell wanted to do, who’d care? The deputies protected Charles Manson, but I was a nobody.

I learned again how injustices might happen for a Chicano street kid from the barrio.

ELVIRA: What advice would you give to families/children who have loved ones in prison?

LUIS: I learned with my son not to abandon him. I couldn’t really save him or protect him from his ordeal, but I had to be there when he needed guidance, mentoring, love, support. In time with Ramiro, he learned to appreciate that the family stood by him all those years he was incarcerated. We’re now very close as a father and son.

ELVIRA: If there is anything positive you can say about gangs, what would you say? What are the negative things about gangs? What are alternative options for young people who want to join or start a gang, especially if they come from a neighborhood or family where the pressure to be “cool” or “down” is always there. In other words, how can you be “down with la raza” in a positive way.

LUIS: Gangs have always existed—they are primarily a community a young men trying to find intensity, meaning, a path to the outer world (outside of home) that most tribal groupings addressed with rituals, rites of passage, initiation ceremonies. We’ve lost this knowledge as a culture. Gangs also exist when there are lots of empties in a person, in family, in community. It points out how we need to do more to bring real art, passions, teachings, caring, and resources into the emptiness of young peoples’ lives.

Gangs, of course, are also tied to suicide, rage, abandonment, abuse at home, neglect, etc. The “Crazy Life” becomes a chain, a web that holds a young person so that his own will and personal power does not matter anymore. If young people had love, hope, true education, the arts, full and meaningful lives they won’t join gangs. My life since living the gang and drugs has been directed to making positive what it means to be Chicano, human, man, woman, and on how to draw out the imagination and creativity that all people have.

Gangs, of course, are also tied to suicide, rage, abandonment, abuse at home, neglect, etc. The “Crazy Life” becomes a chain, a web that holds a young person so that his own will and personal power does not matter anymore. If young people had love, hope, true education, the arts, full and meaningful lives they won’t join gangs. My life since living the gang and drugs has been directed to making positive what it means to be Chicano, human, man, woman, and on how to draw out the imagination and creativity that all people have.

We need more leaders among our gente–more teachers, politicians, businesspeople, organizers, and such. Turn the energy that many young people are putting into “war” and “death” and put it into life and true justice.

ELVIRA: As a teen, you experienced a lot of police brutality, harassment, and profiling. The incident where you tried to help a woman from aggressive cops landed you in jail and led to you dropping out of college and losing your first book contract. What are your views now on police and how they interact with young people from poor and urban neighborhoods? What should be done, if anything, to improve this relationship?

LUIS: We as families and communities cannot slacken our pressures to end police abuse and misuse of power. This abuse continues till this day.

My new book talks about some of the work I did in this area.

But something is also different. Before when I was a child and adolescent, police officers weren’t from our communities. They were mostly white and from other neighborhoods.

This has changed.

I have a niece that’s a police officer. A few friends. They are our neighbors and family. So I try to work with them as well to get them to see how we are all still the same people. If they hurt our kids, this impacts all of us. It did me. But if we see police officers as extensions of the community’s needs, its wellbeing and for peace, they can be an asset. This is harder, again, I tend to go this way. But it works for me. So whatever I do now is not anti-police. It is anti-police abuse, anti-police state, against using police and prisons to answer what are political, sociological, and economic matters.

But police officers are human, too.

I’ve worked with a few of them to better our communities.

ELVIRA: One of your poems that stood out to me is A Father’s Lesson. It’s funny and  I can relate. Was this poem inspired by your own father? What would you like to share about your father and how are you like him or not like him? What do you think is the biggest struggle or challenge for Chicano or Mexican fathers today?

I can relate. Was this poem inspired by your own father? What would you like to share about your father and how are you like him or not like him? What do you think is the biggest struggle or challenge for Chicano or Mexican fathers today?

LUIS: In my new book, I deal more with my father, which I didn’t really get into in Always Running. I had a terrible relationship with him and the new book gets into this more than any other time. That poem was based on a true incident between my father and me (as well my brother). It was one of the funny incidents I recall relating to my dad.

Right now I can only say that my father was very distant and cold to me and my brother–we didn’t relate very well. Later on he did some terrible things that caused me to hate him even more. You need to read the book to find out more.

Chicano/Mexicano fathers have the problem of inheriting the wrong “macho” concept of manhood–that one doesn’t cry, or feel, and being tough is being a man. There’s more being a man than that. More of a real warrior–well-rounded, healthy, loving in a man’s way, and being a great protector, teacher, guide, and creative. I’m not putting down all fathers, of course, but my dad was one of those emotionally-detached fathers. I also had raging issues, which alienated me from my wives, girlfriends, and my kids. Yes, men need to be strong, but not bullies. They need to know how to not get emotionally lost in situations, but not be cold and emotionless. They need to know the full variety of emotions as well as thinking and acting. Not just the most limited ways of doing things.

ELVIRA: In your new book, do you also give an “update” on your sister Shorty and Ana, your brother Joe, and your mom?

LUIS: I do update them, but not by name. I reveal a terrible thing that happened regarding my father. I won’t go into what this is here, but it’s something that my family is divided around and I may get a lot of flack for this.

But I’ve always been prepared to write about the hard things. Only for healing, teaching, and enlightening purposes not to hurt or disparage anyone.

But I’ve always been prepared to write about the hard things. Only for healing, teaching, and enlightening purposes not to hurt or disparage anyone.

Anyway, I was estranged from my family for most of my adult life, so they don’t play much of a role in my new book.

ELVIRA: What would you like us to know about your upcoming book IT CALLS YOU BACK?

LUIS: It’s not Always Running–it’s about my growth into maturity over forty years. There’s much more of my love experiences, both bad and good, my political and artistic development, as well as my growth as a father and husband–and, of course, my battles with addictions to drugs and alcohol over 27 years. One important thing is that I’m now sober for 18 years. My book documents this struggle to be clean, sober, and decent.

ELVIRA: Is there anything else you would like to share?

LUIS: We all need each other. Gangs do try to fill that void–but they can’t do what healthy, balanced, and coherent families and communities can do. Let’s strengthen our core relationships from the start—and all the way through a young person’s life. This is the best way to avoid the growth of deadly and crime-involved gangs. I’m not really anti-gang—I was a gang member and so was my son. I’m pro-youth, pro-community, pro-family, pro-arts, and pro-peace. To go against gangs or drugs is meaningless unless this is mostly done by filling in the empties, the vacuums, and stop the neglect and harm we do as detached, mean, irresponsible adults and communities. The answer is in our hands.