Dr. Thomas Simpson is a Distinguished Senior Lecturer in Italian at Northwestern University and the author of the recent book Murder and Media in the New Rome: The Fadda Affair. Meticulously researched in the libraries and archives of Italy, his book offers a fascinating exploration of “a sensational crime and trial that took place in Rome in the late 1870’s, when the bloody killing of a war hero triggered a national spectacle.” On Thursday, January 31st at 7 p.m., you can hear Dr. Simpson discuss and read from Murder and Media in the New Rome when he visits EPL’s 1st Floor Community Meeting Room as part of the Evanston Northwestern Humanities Lecture Series. In anticipation of his visit, we recently spoke with him via email about how the Fadda Affair fits into the whole of Italian history, how newspapers helped enflame the scandal, the role of Roman women in the spectacle, and the best novels about the “Risorgimento” period.

Dr. Thomas Simpson is a Distinguished Senior Lecturer in Italian at Northwestern University and the author of the recent book Murder and Media in the New Rome: The Fadda Affair. Meticulously researched in the libraries and archives of Italy, his book offers a fascinating exploration of “a sensational crime and trial that took place in Rome in the late 1870’s, when the bloody killing of a war hero triggered a national spectacle.” On Thursday, January 31st at 7 p.m., you can hear Dr. Simpson discuss and read from Murder and Media in the New Rome when he visits EPL’s 1st Floor Community Meeting Room as part of the Evanston Northwestern Humanities Lecture Series. In anticipation of his visit, we recently spoke with him via email about how the Fadda Affair fits into the whole of Italian history, how newspapers helped enflame the scandal, the role of Roman women in the spectacle, and the best novels about the “Risorgimento” period.

Evanston Public Library: Could you give us a brief summary of the events that became known as the Fadda Affair? Also – for the more casual historian – could you place the crime and trial in the greater context of Italian history? What was life like in 1870’s Rome?

Thomas Simpson: In October 1878 a hero of Italy’s war of national unification was stabbed to death in downtown Rome. Near the scene police arrested a blood-spattered circus equestrian who protested his innocence. Word spread that the acrobat was the lover of the soldier’s much younger, Southern wife. She was soon arrested but she too denied the charges, claiming never to have heard the rumor that her husband’s war wound had left him impotent. Police soon arrested a second woman, another circus equestrian, who was alternately described as the acrobat’s sister and his wife. Newspapers seized on the story, having discovered that newly literate readers preferred scandalous stories to reports of debate in Parliament. When the trial opened, people were stunned by the masses of women who crowded the courtroom to witness the testimony and stare at the accused wife, who wept throughout the proceedings. Why were women – who should have been home looking after their children – so fascinated with the disgraceful circumstances of the trial, and what did this bode for the young nation of Italy?

To put the crime and trial in greater context, Italy – though an ancient land – only became a unified nation in 1861, and Rome only became the capital a decade later. Open trials with prosecuting and defense attorneys were a new phenomenon, coming at the same moment that newspapers discovered readers’ preference for crime news. The trial struck deep at the heart of social divisions that marked the whole process of Italian independence, which many regarded not as an American-style revolution, but as a war of conquest of the North over the South. The murder by a Southern wife of her impotent Northern husband enacted the hidden social tensions that put at risk the very nationhood of Italy.

EPL: What first sparked your interest in the Fadda Affair, and what motivated you to write Murder and Media in the New Rome? Could you give us a window into your research process?

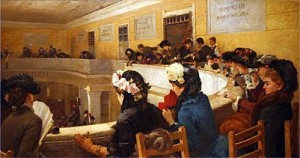

TS: In a small southern museum I discovered a painting, “In Corte d’Assise”, that shows a crowd of well-dressed women breathlessly watching a trial in which the accused is another woman, much like themselves. Tracing the subject of the painting led me to the trial archives in Rome and to the newspapers that covered the trial’s daily sessions.

EPL: Speaking of Roman newspapers, you present a fascinating selection of historical coverage of the trial in Chapter 3, “Chronology of a Circus Trial.” Can you touch on how newspaper reporting helped shape the public’s perception of the affair? What other forms of media were influential?

TS: One particularly interesting aspect of the story is that most of the populace was illiterate, so that a lot of people followed the trial by listening to others read the daily newspaper trial reports aloud in cafés throughout the peninsula. This fact puts into relief the choral aspect of how the entire nation fixated on this story. Another crucial form of media that shaped the reaction to the trial was the poem published in newspapers by the Italian bard of the national unification movement, Giosue Carducci, who adopted an ancient form of Latin poetry to condemn the women spectators.

EPL: Why were Roman women so drawn to the Fadda Affair, and why was their interest so scandalous?

TS: Some argue that women attended the trial in droves because this was the only way for them to participate actively in the democratic process. After all, women could not vote, could not serve as judge, lawyers, or jury; even their testimony in court had only been considered legally probative since 1877. Others argued that women were fascinated because they identified with the accused wife at the center of the scandal.

EPL: In your Introduction you write, “Judges, lawyers, witnesses, jury and public; all were quite conscious that they were wearing costumes, representing something, and performing.” What inspired these theatrical inclinations? How did these “performances” help enflame the spectacle?

TS: As with all media circuses, the importance of the event grows with the amount of attention the media attaches to it. The excitement feeds on itself, exploding out of proportion with the import of the tawdry facts of the case. As with media circuses in the US that we are all familiar with, the real characters at the center of the story become secondary to all the symbolic baggage that spectators load them down with. It’s like a Pirandello play in some ways.

EPL: What lasting influence did the Fadda Affair have on Italy and Rome? Why do you think the crime and trial have largely been forgotten or ignored by modern scholars?

TS: This is a question about what historians decide is important to study. The Fadda Affair was an embarrassment to the young nation, its international image, and more importantly, its own self -image. It seems to us in America that what goes on in the halls of Congress is what we’re supposed to know about, rather than the trivialities of pop culture. But what really tells our story? That’s the intriguing question.

EPL: What do you hope readers will to take away from Murder and Media in the New Rome? Can you suggest additional books or resources for those interested in learning more about this moment in Italian history?

EPL: What do you hope readers will to take away from Murder and Media in the New Rome? Can you suggest additional books or resources for those interested in learning more about this moment in Italian history?

TS: This period of Italian history has been much less studied, relative to the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Twentieth Century, but there has been a recent groundswell of interest in the “Risorgimento,” the period of the unification wars. The best book to read about this period is a novel, The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa – made into a great 1963 film starring Burt Lancaster and Claudia Cardinale. There is no really good book or novel that I know of about the post-Risorgimento period, from 1871 till more or less the beginning of the century, but a great writer of this period is Giovanni Verga, whose short stories are fantastic. I Malavoglia, about a family of Sicilian fisherman, is his most famous book, and another novel Mastro-Don Gesualdo is more specifically about changing national character in this period.

Interview by Russell J.