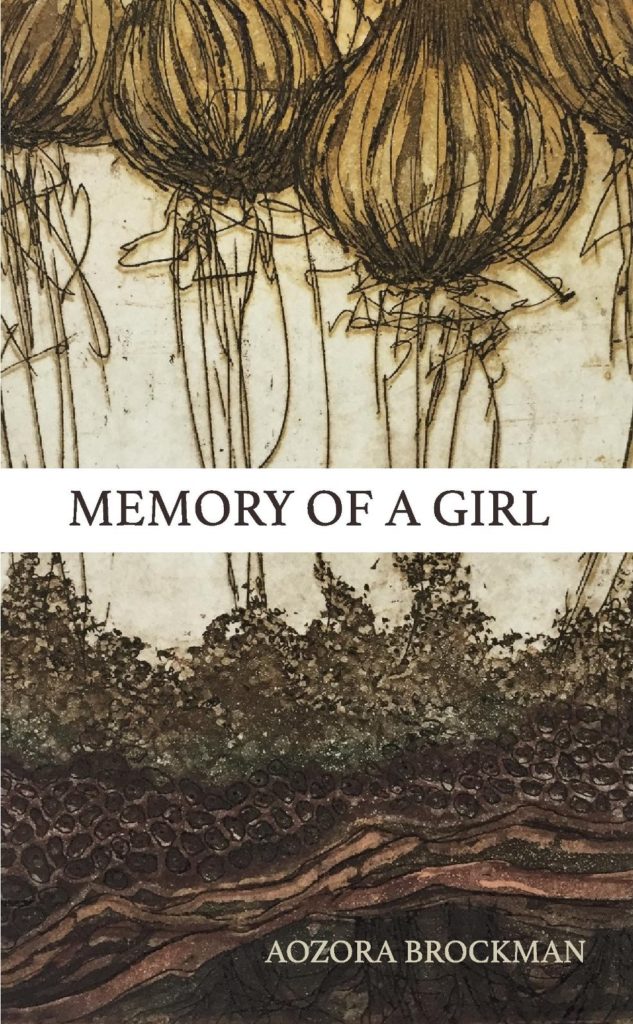

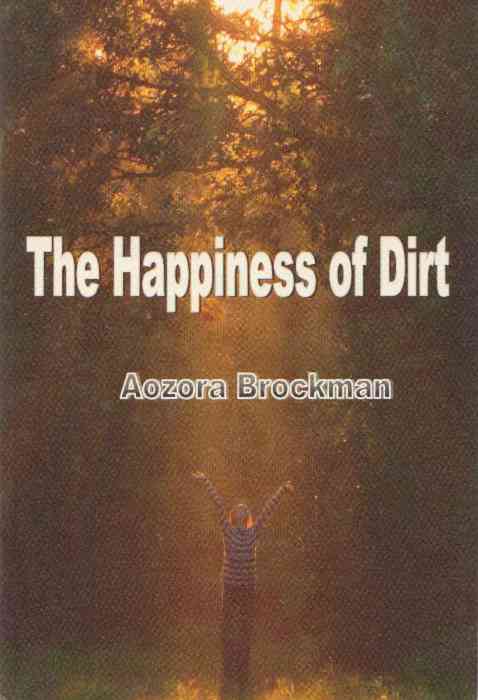

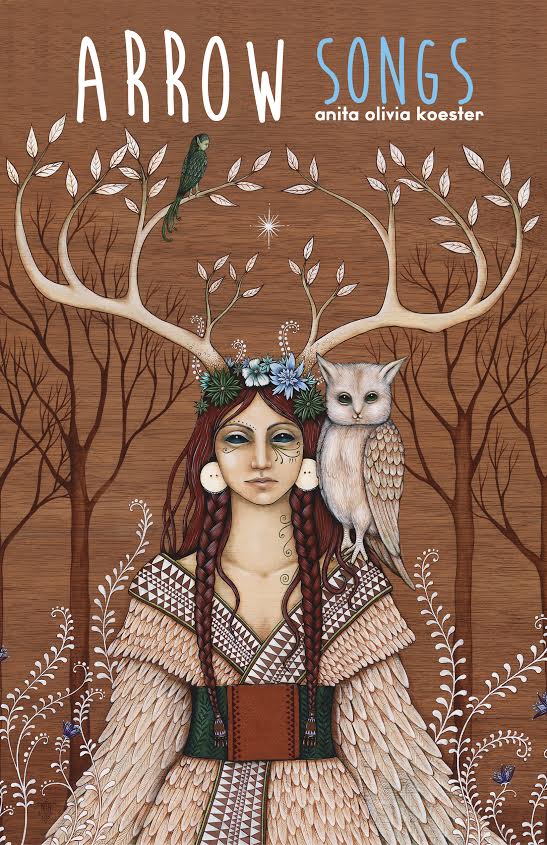

Even though National Poetry Month is winding down, we’re not done celebrating here at EPL. This Sunday, April 30 at 4 pm we’re thrilled to welcome poets Aozora Brockman and Anita Olivia Koester as part of the 2017 Evanston Literary Festival. Both will read from their latest collections, and in anticipation, we recently spoke with Brockman via email. Raised on an organic vegetable farm in Central Illinois, Brockman is the author of two chapbooks, The Happiness of Dirt and Memory of a Girl. She is the recipient of the 2015 Jean Meyer Aloe Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets, and her poems have been published in the Cortland Review, Fifth Wednesday, Reckoning and other journals. She lives, works, and writes in the haven of her family’s farm. You can learn more by visiting her website, and below she discusses her poetic origins and inspirations, her writing process, and her superb poem “Bottomland.” Enjoy!

Even though National Poetry Month is winding down, we’re not done celebrating here at EPL. This Sunday, April 30 at 4 pm we’re thrilled to welcome poets Aozora Brockman and Anita Olivia Koester as part of the 2017 Evanston Literary Festival. Both will read from their latest collections, and in anticipation, we recently spoke with Brockman via email. Raised on an organic vegetable farm in Central Illinois, Brockman is the author of two chapbooks, The Happiness of Dirt and Memory of a Girl. She is the recipient of the 2015 Jean Meyer Aloe Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets, and her poems have been published in the Cortland Review, Fifth Wednesday, Reckoning and other journals. She lives, works, and writes in the haven of her family’s farm. You can learn more by visiting her website, and below she discusses her poetic origins and inspirations, her writing process, and her superb poem “Bottomland.” Enjoy!

EPL: Can you tell us a little about your background as a poet? What started you writing poetry? What did you write about when you began, and what do you write about now?

Aozora Brockman: My very first poems emerged as improvised songs when I was young. Some winter evenings, as I went out to feed and water our chickens and goats, the rhythm of my feet crunching on the packed snow set a beat, and my arm swinging my empty egg pail added a counterpoint. When I opened my mouth, words would come tumbling out and follow a melody I made up on the spot.

I am easily overwhelmed by sensations and sounds, so spending whole days cooped up in the house in the winter listening to the constant chatter of public radio made me feel like a helium balloon blown too full. So I loved those rare moments of solitude and silence, when it was just me and the moon and the snow, when all of the words that I had shoved down inside of my throat floated out into the cold air. Most of the time the words were strung together randomly and didn’t make a lot of sense, but at times I found myself singing thoughts and feelings that reflected deeply what I needed right then to express.

I think this is what I love most about writing poetry—sometimes, when you sit down with a pen and paper and allow yourself to write whatever comes into your mind, you discover something deep inside of you that needed to come out into the world. Suddenly something clicks into place, and whatever was vague inside your mind is now concrete, right on the page. I’ve been hooked on that feeling—of empowerment, and joy—since I was young, and that has kept me writing.

I think this is what I love most about writing poetry—sometimes, when you sit down with a pen and paper and allow yourself to write whatever comes into your mind, you discover something deep inside of you that needed to come out into the world. Suddenly something clicks into place, and whatever was vague inside your mind is now concrete, right on the page. I’ve been hooked on that feeling—of empowerment, and joy—since I was young, and that has kept me writing.

But it wasn’t until I took a class with Rachel Jamison Webster through the Creative Writing program at Northwestern that I dared to think of myself as a poet. Growing up, I felt there was a clear difference between poems that I read in school—which oftentimes confounded me—and what I was writing. I used poems as a kind of short-hand for longer essays, and I hardly knew what I was doing with form or enjambment or rhythm. I remember that I was terrified of taking the Reading and Writing Poetry course with Rachel because I thought I would fail at writing “good” poems. Thankfully, I was wrong! Not only did Rachel convince me that I was capable of writing poetry, but she also encouraged me to delve deeper into myself and to write with sensitivity and bravery. She taught me that there was great freedom in writing poetry—that I could be wholly, unabashedly, myself—and that poetry has the power to rupture structures, to heal, and to make people feel tremendous emotion.

The poems I wrote before meeting and learning from Rachel were more reserved and filled with imagery of the vegetable fields of our farm. I still derive inspiration from the beauty of our family farm, but the poems I write now are emotionally open and probing.

EPL: Can you give us a window into your writing process? How do you begin, and what are the essential ingredients of a good poem? Has your idea of what poetry is changed since you began writing?

AB: Ideas for poems often come to me when I’m weeding or harvesting on our farm. The repetitive movements of swiping a hand hoe around seedlings and brushing dirt up against them, or gathering up a bouquet of pink beauty radish and twirling a twist-tie around them engages my body and mind in such a way that I feel intimately connected to the dirt, bugs, birds and woods that surround me. This meditative space is conducive to poetic inspiration.

Sometimes I see something gorgeous and fall in love—a butterfly emerging from a emerald cocoon or a spider spinning an intricate web—and have to write about it, or sometimes I am digging up sweet potatoes and the joy of it sparks an idea. My father likes to say that when he’s working on the farm, he’s not composing songs or writing the next great American novel, but that his mind is essentially blank, fully concentrated on the task before him. I’m not writing poetry while I’m working either, but something about being completely engaged, on hands and knees in dirt, allows my mind to wander off and settle on an idea. Most of the time I am so busy on the farm that I forget the idea or image during the course of a physically intense work day, but usually it comes back to me again while working in the field and sticks in my memory.

Sometimes I see something gorgeous and fall in love—a butterfly emerging from a emerald cocoon or a spider spinning an intricate web—and have to write about it, or sometimes I am digging up sweet potatoes and the joy of it sparks an idea. My father likes to say that when he’s working on the farm, he’s not composing songs or writing the next great American novel, but that his mind is essentially blank, fully concentrated on the task before him. I’m not writing poetry while I’m working either, but something about being completely engaged, on hands and knees in dirt, allows my mind to wander off and settle on an idea. Most of the time I am so busy on the farm that I forget the idea or image during the course of a physically intense work day, but usually it comes back to me again while working in the field and sticks in my memory.

When I sit down to write, I close my eyes and think of an image or scene that struck me. I try to remember how it felt to be in that moment: what I was touching, what I was smelling, what colors I was mesmerized by, what voices or sounds I was hearing. Then, with words, I try to recreate that memory as vividly as possible so that it can enter into someone else’s mind. To do that, I have to translate images and hard to describe feelings into language—which takes a lot of trial and error. But I always want my reader to be right there with me, feeling and seeing and hearing through my eyes and body.

For me, the most essential ingredient to writing a good poem is an openness to, sensitivity towards, and love for the world around me. If I am closed off to the world, or fearful and anxious of what surrounds me, my poems become one-dimensional or forceful. Because I fear something, I want to see the world without depth and ignore the complex chaos just below the surface. This way of seeing and feeling makes my poetry substanceless and devoid of truth. I believe the best poetry does not try to bang the reader over the head with an argument, but rather reflects the world in all of its complexity, even if it reveals something ugly or heartbreaking.

I haven’t always felt that poetry was so connected to love and openness—in fact, I think I’ve just recently come to this conclusion. It has been almost two years since I graduated from college, and for most of that time, I found it very difficult to write poetry. As a young adult facing the realities of climate change, political instability, racism, sexism and everything else, I felt an immense weight on my shoulders, and, filled with terror about my future, I retreated inside myself. But this spring, I finally feel myself opening up again, and love and hope are brimming in my heart. Poetry is brimming in me, too, because for the first time in a long while, I am seeing the world clearly and with care, and I want so much to share what I am seeing and feeling, and to connect with others. Poetry, it seems, is all about wanting to connect, and though I probably knew this on the surface-level before, I know this with conviction now.

EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?

EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?

AB: Rachel Webster inspires me immensely. Her poems quicken my heart when I’m reading them, and images and thoughts and feelings grow so big inside of me that I have to put her book down to write a poem myself. I feel very connected to her poetry, and that bond lets me break free from where I am stuck in my mind, and hurtles me into a new realm of thought.

I also love Joy Harjo’s poetry, and Audre Lorde’s poem “Power” is one of my all-time favorites. The work of Anne Sexton, Franny Choi, Nicky Finney and June Jordan fascinate and inspire me.

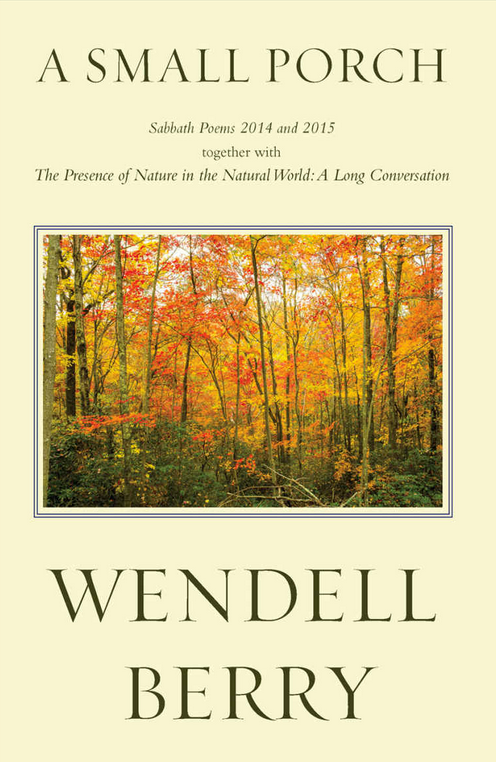

I am reading Wendell Berry’s A Small Porch right now, which is a joy! My grandpa, Herman, adores Wendell Berry and he and my grandma Marlene gifted all six of their children with a copy of the book this past Christmas. My grandpa, who is an avid lover of poetry, always asks me when I see him if I’ve finished reading the book yet. I’m happy to say I am now halfway through it! As a farmer-poet, Wendell Berry infuses his poems with the cycles of the seasons and laments our destruction of the earth. As my grandpa explains it, instead of going to church on Sundays with his wife, Berry spends his Sabbath walking in woods or sitting on his porch, writing poems. I am inspired by this idea and hope to be a farmer-poet like Berry someday.

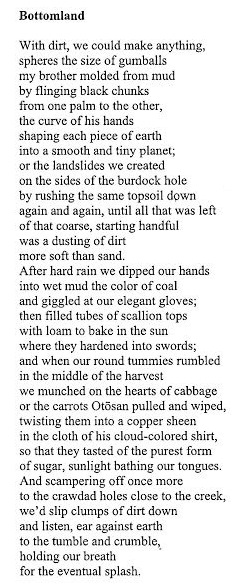

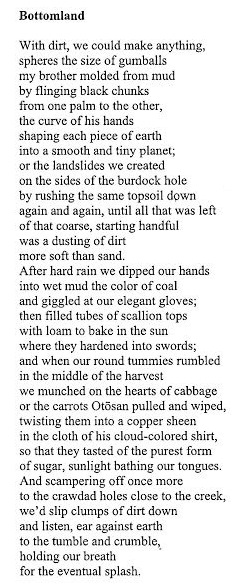

EPL: Can you tell us a bit about the poem you chose to share?

AB: “Bottomland” is a love poem to the black loamy dirt of our fields, and to my brothers, Asa and Kazami, who played in the dirt with me when we were still too young to help out on the farm. I found with this poem that it is very difficult to describe how we played with the dirt, and the joy of it, to a reader who isn’t intimately familiar with our farm. I mention a “burdock hole” in the poem, for instance, and I am sure that most people have never even heard of burdock, much less know how it is harvested.

Burdock, called gobo in Japanese, is a long black root that extends up to three feet into the ground. To harvest it, we take spades and shovels and dig out around the three rows of burdock, careful not to cut through the roots in the process. The deep and wide hole that remains after we’ve dug out all of the burdock looks almost like a grave. When my brothers and I were little, we’d be just as tall as the hole, and while my dad—who I call Otōsan—hurled shovel after shovel of dirt out of the hole, we would have nothing to do but immerse ourselves in the soil all around us: feeling it, smelling it, looking at it up close, or even tasting it. (My brother Kazami was infamous for eating handfuls of dirt!)

During one of those burdock harvests, Asa noticed how some of the dirt Otōsan piled up next to the hole came trickling down the side of it, and since the edge of the hole wasn’t perfectly smooth, the streams of dirt would catch on little knobs and ruts on the way down. Asa showed me how to take a handful of dirt and let it run down the side of the hole, then gather it up from the bottom and run it down again and again. We observed how the finest dirt would settle on the knobs and ruts while the coarser dirt would tumble all the way to the bottom of the hole, and something about this process was beautiful and fascinating to us. I loved to touch the dirt that coated the knobs and marvel at its rabbit-fur-like softness.

When Asa read Memory of a Girl, he told me “Bottomland” was his favorite poem and that it made him nostalgic for our childhood. I wrote “Bottomland” to remember and relive the most joyous moments of growing up on our farm, and the poem makes me nostalgic too. What I miss most is being able to derive so much happiness from playing with what surrounded us—dirt. Since not many people grew up playing the way we did, it is easy to feel that what I remember from my childhood is imagined or not real. But “Bottomland” allows me to capture those memories, and live again the days when the bottomland field was my whole world.

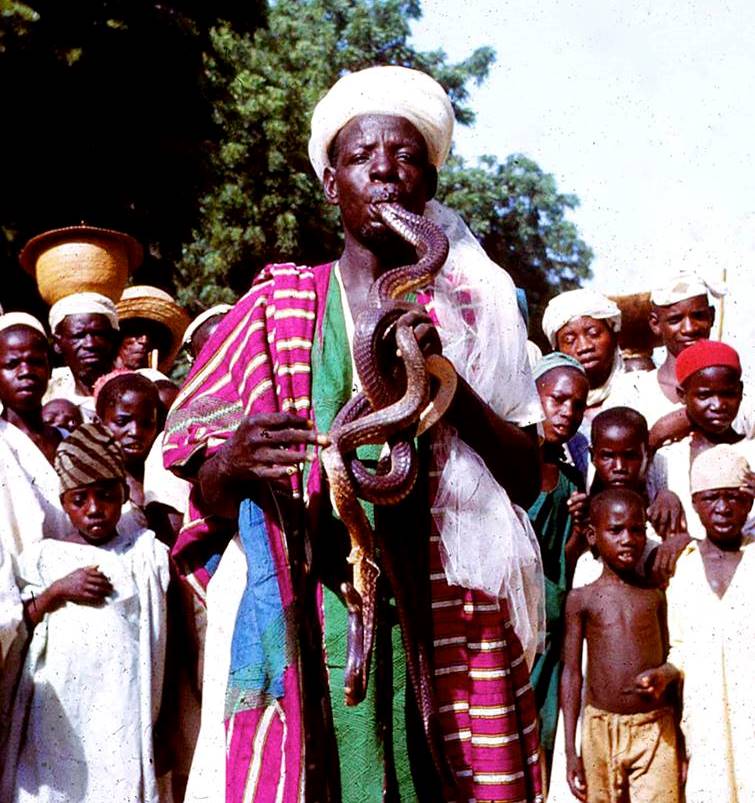

Charles McCleanon is a local photographer who is the latest to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. A Chicago native and a retired Dean of Information Technology at City Colleges, McCleanon’s appreciation of 35 mm film inspired him to begin his photography career 25 years ago. He formed the company CGMcPhoto and began shooting political campaigns, street fairs, weddings, and community events. He eventually channeled his skills into digital photography and now combines his talents with a passion for travel that’s resulted in countless breathtaking images. You can catch his show through the end of October on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Library and meet him at a closing reception at 7 pm on Wednesday, October 25. We recently spoke with him via email about his artistic origins, creative process, and future photography goals.

Charles McCleanon is a local photographer who is the latest to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. A Chicago native and a retired Dean of Information Technology at City Colleges, McCleanon’s appreciation of 35 mm film inspired him to begin his photography career 25 years ago. He formed the company CGMcPhoto and began shooting political campaigns, street fairs, weddings, and community events. He eventually channeled his skills into digital photography and now combines his talents with a passion for travel that’s resulted in countless breathtaking images. You can catch his show through the end of October on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Library and meet him at a closing reception at 7 pm on Wednesday, October 25. We recently spoke with him via email about his artistic origins, creative process, and future photography goals.

Jim Parks is an Evanston artist who is the latest to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. In 2015 – after a long career in theater, radio, and television as the host of HGTV’s “New Spaces” – he converted his dining room into a studio and devoted himself “to producing the art that had been waiting inside all those years.” You can catch his exhibit The Bloomz Collection through the end of August on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Library, and you can find more of his nature-inspired acrylic paintings by visiting

Jim Parks is an Evanston artist who is the latest to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. In 2015 – after a long career in theater, radio, and television as the host of HGTV’s “New Spaces” – he converted his dining room into a studio and devoted himself “to producing the art that had been waiting inside all those years.” You can catch his exhibit The Bloomz Collection through the end of August on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Library, and you can find more of his nature-inspired acrylic paintings by visiting

Even though National Poetry Month is winding down, we’re not done celebrating here at EPL. This

Even though National Poetry Month is winding down, we’re not done celebrating here at EPL. This  I think this is what I love most about writing poetry—sometimes, when you sit down with a pen and paper and allow yourself to write whatever comes into your mind, you discover something deep inside of you that needed to come out into the world. Suddenly something clicks into place, and whatever was vague inside your mind is now concrete, right on the page. I’ve been hooked on that feeling—of empowerment, and joy—since I was young, and that has kept me writing.

I think this is what I love most about writing poetry—sometimes, when you sit down with a pen and paper and allow yourself to write whatever comes into your mind, you discover something deep inside of you that needed to come out into the world. Suddenly something clicks into place, and whatever was vague inside your mind is now concrete, right on the page. I’ve been hooked on that feeling—of empowerment, and joy—since I was young, and that has kept me writing. Sometimes I see something gorgeous and fall in love—a butterfly emerging from a emerald cocoon or a spider spinning an intricate web—and have to write about it, or sometimes I am digging up sweet potatoes and the joy of it sparks an idea. My father likes to say that when he’s working on the farm, he’s not composing songs or writing the next great American novel, but that his mind is essentially blank, fully concentrated on the task before him. I’m not writing poetry while I’m working either, but something about being completely engaged, on hands and knees in dirt, allows my mind to wander off and settle on an idea. Most of the time I am so busy on the farm that I forget the idea or image during the course of a physically intense work day, but usually it comes back to me again while working in the field and sticks in my memory.

Sometimes I see something gorgeous and fall in love—a butterfly emerging from a emerald cocoon or a spider spinning an intricate web—and have to write about it, or sometimes I am digging up sweet potatoes and the joy of it sparks an idea. My father likes to say that when he’s working on the farm, he’s not composing songs or writing the next great American novel, but that his mind is essentially blank, fully concentrated on the task before him. I’m not writing poetry while I’m working either, but something about being completely engaged, on hands and knees in dirt, allows my mind to wander off and settle on an idea. Most of the time I am so busy on the farm that I forget the idea or image during the course of a physically intense work day, but usually it comes back to me again while working in the field and sticks in my memory. EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?

EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?

Kristen Neveu is an Evanston artist who is the latest to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. A painter and collage artist whose work has shown at

Kristen Neveu is an Evanston artist who is the latest to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. A painter and collage artist whose work has shown at

April is National Poetry Month, and here at EPL we’re celebrating with a very special poetry event. On

April is National Poetry Month, and here at EPL we’re celebrating with a very special poetry event. On  EPL: Can you give us a window into your writing process? How do you begin, and what are the essential ingredients of a good poem? Has your idea of what poetry is changed since you began writing?

EPL: Can you give us a window into your writing process? How do you begin, and what are the essential ingredients of a good poem? Has your idea of what poetry is changed since you began writing?  EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?

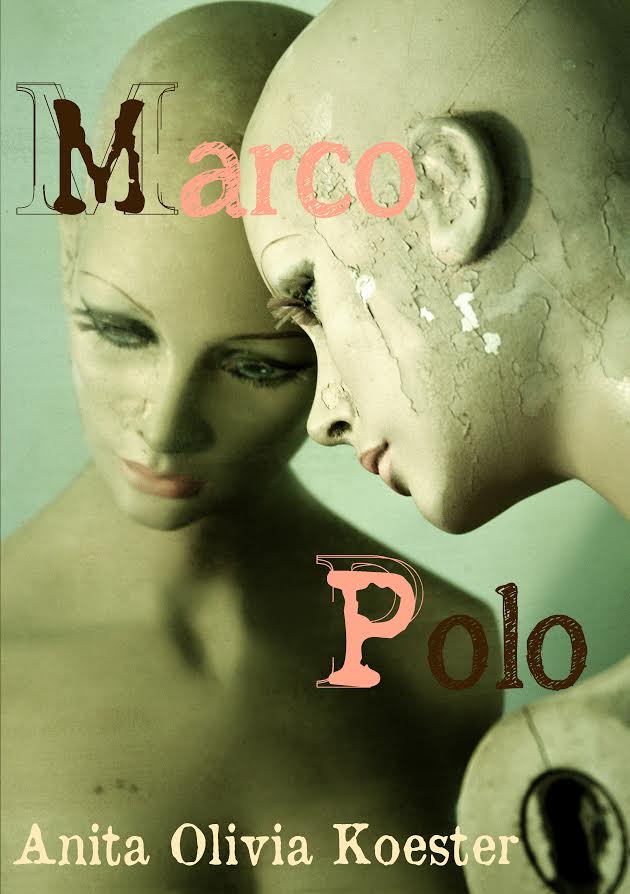

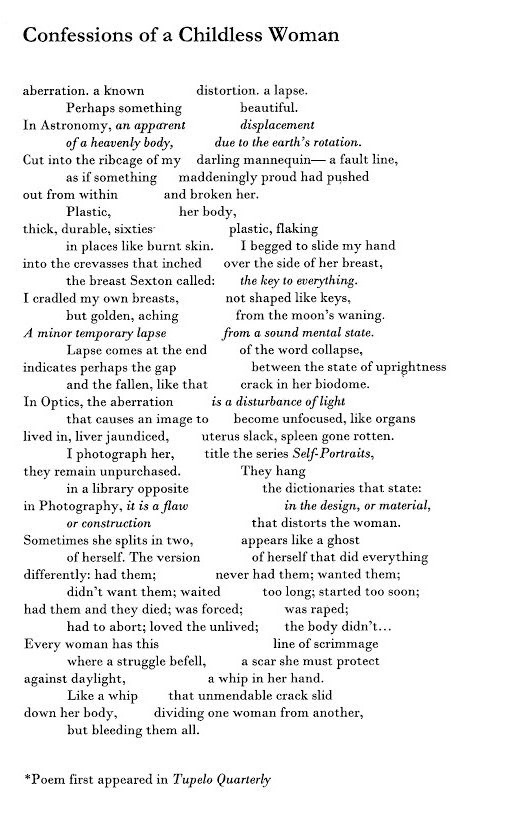

EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?  I spent a great deal of time both shooting and editing the series, as well as printing, framing, and exhibiting them, and now since I’m too lazy to find them another home, they decorate my apartment. The crack running down the one mannequin’s rib cage and breast has so occupied my imagination I’m sure I’ve dreamt about it. In some ways it was cathartic to take some of my emotions and place them on these mannequins, and in other ways it left me exposed and vulnerable. It gave a kind of physical shape to my own psychic pain. One of these photos became the cover of my first chapbook, Marco Polo, and other ones have gone on to be published in journals and books, though I never sold one of the prints, I think in part because they can be disturbing, though not to me.

I spent a great deal of time both shooting and editing the series, as well as printing, framing, and exhibiting them, and now since I’m too lazy to find them another home, they decorate my apartment. The crack running down the one mannequin’s rib cage and breast has so occupied my imagination I’m sure I’ve dreamt about it. In some ways it was cathartic to take some of my emotions and place them on these mannequins, and in other ways it left me exposed and vulnerable. It gave a kind of physical shape to my own psychic pain. One of these photos became the cover of my first chapbook, Marco Polo, and other ones have gone on to be published in journals and books, though I never sold one of the prints, I think in part because they can be disturbing, though not to me.

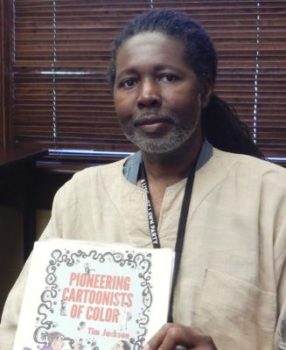

Tim Jackson knows a thing or two about cartoons. A syndicated editorial cartoonist whose work has appeared in the Chicago Defender, Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati Herald, and many other newspapers, Jackson recently became a cartoon historian with the publication of his book

Tim Jackson knows a thing or two about cartoons. A syndicated editorial cartoonist whose work has appeared in the Chicago Defender, Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati Herald, and many other newspapers, Jackson recently became a cartoon historian with the publication of his book  David Pritchett is an Evanston educator and photographer who made his

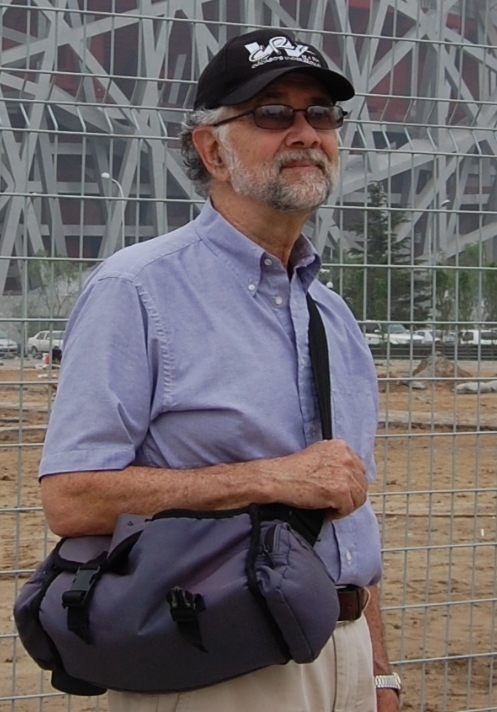

David Pritchett is an Evanston educator and photographer who made his

If Amy Newman’s

If Amy Newman’s  On the rainy evening of September 27, 1999, Dr. Clark Elliott was en route to DePaul University to deliver a lecture when his car was rear ended at a Morton Grove stoplight. Shaken but seemingly uninjured, Elliott continued on to DePaul’s campus unaware he’d suffered a concussion that would dramatically alter his life. In his remarkable new memoir

On the rainy evening of September 27, 1999, Dr. Clark Elliott was en route to DePaul University to deliver a lecture when his car was rear ended at a Morton Grove stoplight. Shaken but seemingly uninjured, Elliott continued on to DePaul’s campus unaware he’d suffered a concussion that would dramatically alter his life. In his remarkable new memoir