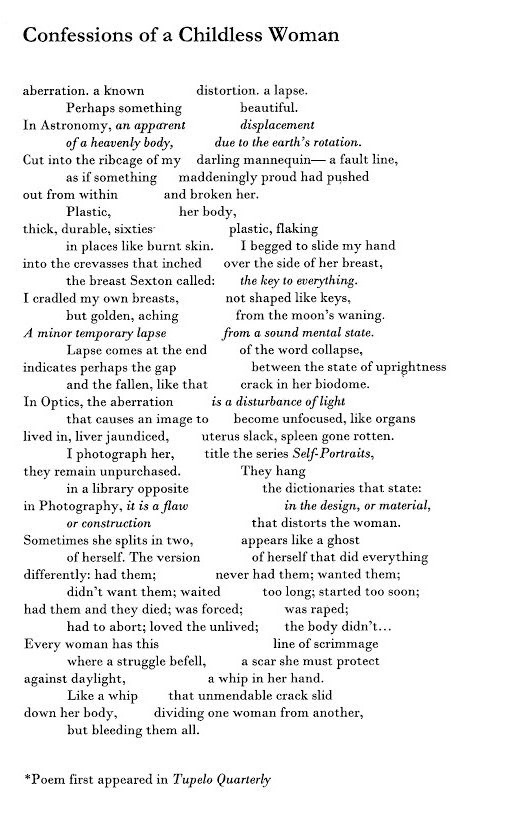

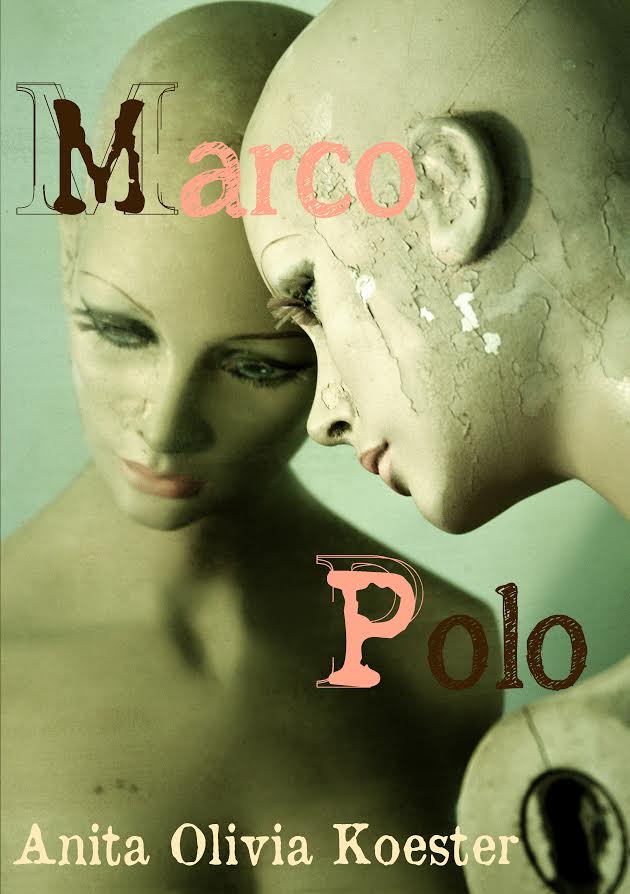

April is National Poetry Month, and here at EPL we’re celebrating with a very special poetry event. On Sunday, April 30 at 4 pm we’re excited to welcome poets Anita Olivia Koester and Aozora Brockman as part of the 2017 Evanston Literary Festival. Both will read from their latest collections, and in anticipation, we recently spoke with Koester via email. A Chicago poet and editor for the lit journal Duende, Koester is the author of the chapbooks Marco Polo, Apples or Pomegranates (forthcoming), and Arrow Songs which won Paper Nautilus’ Vella Chapbook Contest. She is the recipient of Midwestern Gothic’s Lake Prize, the Jo-Anne Hirshfield Memorial Poetry Award, and the Bread Loaf Returning Contributors Award, and her poetry is published or forthcoming in Vinyl, Tahoma Literary Review, CALYX Journal, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. You can learn more by visiting her website, and below she discusses her poetic origins and inspirations, her writing process, and her excellent poem “Confessions of a Childless Woman.” Enjoy!

April is National Poetry Month, and here at EPL we’re celebrating with a very special poetry event. On Sunday, April 30 at 4 pm we’re excited to welcome poets Anita Olivia Koester and Aozora Brockman as part of the 2017 Evanston Literary Festival. Both will read from their latest collections, and in anticipation, we recently spoke with Koester via email. A Chicago poet and editor for the lit journal Duende, Koester is the author of the chapbooks Marco Polo, Apples or Pomegranates (forthcoming), and Arrow Songs which won Paper Nautilus’ Vella Chapbook Contest. She is the recipient of Midwestern Gothic’s Lake Prize, the Jo-Anne Hirshfield Memorial Poetry Award, and the Bread Loaf Returning Contributors Award, and her poetry is published or forthcoming in Vinyl, Tahoma Literary Review, CALYX Journal, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. You can learn more by visiting her website, and below she discusses her poetic origins and inspirations, her writing process, and her excellent poem “Confessions of a Childless Woman.” Enjoy!

Evanston Public Library: Can you tell us a little about your background as a poet? What started you writing poetry? What did you write about when you began, and what do you write about now?

Anita Olivia Koester: I published my first poem in December 2013, and I would say it was my first or second serious poem. Before that I wrote poems here and there, but had always intended to be a novelist and therefore I read novels. I hardly knew how to read a poem back then, nor had I been exposed to much contemporary poetry. That poem was unlike anything that came after it, mostly because it was written as a fictional poem and from a man’s perspective. I haven’t written a poem from a male’s perspective since. My poems, though often mythical and imaginative, are essentially autobiographical. And I suppose in some ways that first poem was as well, as it was about a husband who cheats on his wife and is experiencing an almost paralytic guilt. Sometimes acquiring empathy for the people who have hurt us can begin the healing process.

Though I had known since childhood that my desire was to become a writer, it wasn’t until I divorced that I was able to start out on the journey to finding my own voice. And many of my poems revisit this theme, the odyssey of a woman in search of her voice, the many beasts she must slay along the way both societal and internal. And for me this journey involves a tremendous amount of loss, and even guilt for leaving one life behind for another. When I first started writing, I was writing fiction, and then I began performing poems at open mics when I lived for a time in Paris. Even though I was always nervous to go up on stage, I loved how immediate the emotional connection could be with other like-minded people. If I read a poem about my father people would come up to me afterwards to tell me about their fathers, and there was a palpable feeling of celebration of emotion and language that I had never known in my life. Nor had I ever felt part of a community before, when I was married I lived an isolated life. I suppose I started writing poetry because of poets, because poets are some of the most welcoming, curious, and interesting people I’ve ever met, and in many ways it felt to me like I had discovered a new family.

EPL: Can you give us a window into your writing process? How do you begin, and what are the essential ingredients of a good poem? Has your idea of what poetry is changed since you began writing?

EPL: Can you give us a window into your writing process? How do you begin, and what are the essential ingredients of a good poem? Has your idea of what poetry is changed since you began writing?

AOK: I feel like my process is always changing, not necessarily developing, but changing. I don’t allow myself to ever say I can only write in one state, and therefore I can allow writing to happen at any time and in any place. I probably write more often than not at home on my computer, but I compose poems on walks to the park, on trains, on planes, in the morning, just as I’m falling asleep, in the shower, while I’m washing dishes. And many times those poems are never put to paper, they just form within me and drift off or perhaps lay in wait (I doubt it though, since I have a terrible memory). But if the piece strikes an emotional cord with me, eventually I will find my way to my phone or computer to write it down, I wish I could say I still wrote on paper, but it’s become a rare occurrence. Not all of these compositions become poems, and even those that do, do not always get sent off to journals. But, they will stay in my files and when I’m feeling stuck I can look to them for lines, words, or images.

Occasionally I write a poem that never has to be revised or reworked, and often times these are my best poems. But even then they’re usually built off the back of lesser poems, I might write five or ten poems on one subject before I finally write the poem that gets it right. And then there are the poems that go through countless drafts, and that is when poetry is like chipping away at a boulder in order to end up with one good quality nugget. Sometimes the poem can seem so small in comparison to the process of arriving at it.

I couldn’t possibly claim that my poems always have the essential ingredients, but when I read poems, I respond to the emotional quality of them first. I always want to be moved by a poem. Beyond that, it varies. I’m personally fond of lyric poetry, poetry that is concerned with the musical elements of a poem – syntax, alliteration, prosody, assonance, slant rhymes, anaphora, repetition, and such. I like to be transported or enraptured by the language itself even at the expense of meaning. For me, the words should dance, or sing, or at the very least sway and hum. I’ll take those poems over poems of wisdom any day. Knowledge can be rather cold. I’d rather read a person’s messy and scattered thoughts that in the end only culminate in experience than be told anything definitive by a poem.

I think my understanding of poetry and poetics has deepened immeasurably since I started writing poetry, and I still have much to learn. It’s one of the things I love about poetry, the continual discovery of just how many ways there are to write something as common and as oft-written as a love poem. It’s hard to appreciate a poem until you’ve read a thousand of them, but once you’ve read a thousand of them, you can’t wait to read a thousand more and go back and read that first thousand again and again. Poems alter depending on the reader and their engagement of it, where they are in their life and what they are feeling, and in that way the life of a poem – as long as it is being read somewhere by someone – is endless.

EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?

EPL: What poets have inspired you? What are you reading right now?

AOK: Oh gosh, I’m always reading 10-30 books at a time. I’m an exceptionally slow reader of poetry, and one reason I love chapbooks is that I can sometimes finish them in a sitting or a few days. Otherwise, I can spend months reading a book of beautiful poems. Each poem is often like a long story compressed, and sometimes I’m so emotionally exhausted after engaging with one knock-out poem that I have to put the book down. (I don’t recommend reading this way at all.) In order to force myself out of this way of reading I sometimes sit at the park and just read a book of poems out loud from cover to cover and let it wash over me without allowing myself to overthink or analyze which I can always do later. We had precious few warm days this winter in Chicago, but on the last warm day I went to the park and read Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds, which is a remarkable book for both the gentle quality within the strength of his voice and for how diverse it is formally. Another one of my favorite books that came out this year was Joshua Bennett’s The Sobbing School, which I might be reading for years since each poem is so emotionally intense it’s like a kick to the stomach and yet the poems are also complex and intellectual.

Other books currently on my nightstand include, Natalie Diaz’s When My Brother Was an Aztec, Roger Reeve’s King Me, Marianne Boruch’s Eventually One Dreams the Real Thing, Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello’s Hour of the Ox, and Jennifer S. Cheng’s House A. And then there are those poets that my poetic universe revolves around, and those currently are Sharon Olds, Pablo Neruda, Adrienne Rich, and Larry Levis.

EPL: Can you tell us a bit about the poem you chose to share?

AOK: “Confessions of a Childless Woman” has a rather long history. It began at the first writing residency I ever went to, a magical place tucked away amid the cornfields of Nebraska called Art Farm. Because I had all this time to create and was surrounded by visual artists, I found myself inspired to do a photo shoot with a number of vintage mannequins I found on the property. Some of the torsos were in the trunk of an abandoned Peugeot which smelled rank when I opened the rusted latch to pull them out. It was the kind of place where you might find some odd pile of materials to repurpose, basically a creative person’s ideal setting. And this one mannequin in particular spoke to me because of a crack she had running down her side. That mannequin – and one other with a beautiful though weatherworn face – became the main subjects of a self-portrait series I did in which the mannequins were placed in various roles I’ve lived. I’ve exhibited this series in a few places in Chicago including the public library, and people always remark on how eerily emotional the mannequins seem.

I spent a great deal of time both shooting and editing the series, as well as printing, framing, and exhibiting them, and now since I’m too lazy to find them another home, they decorate my apartment. The crack running down the one mannequin’s rib cage and breast has so occupied my imagination I’m sure I’ve dreamt about it. In some ways it was cathartic to take some of my emotions and place them on these mannequins, and in other ways it left me exposed and vulnerable. It gave a kind of physical shape to my own psychic pain. One of these photos became the cover of my first chapbook, Marco Polo, and other ones have gone on to be published in journals and books, though I never sold one of the prints, I think in part because they can be disturbing, though not to me.

I spent a great deal of time both shooting and editing the series, as well as printing, framing, and exhibiting them, and now since I’m too lazy to find them another home, they decorate my apartment. The crack running down the one mannequin’s rib cage and breast has so occupied my imagination I’m sure I’ve dreamt about it. In some ways it was cathartic to take some of my emotions and place them on these mannequins, and in other ways it left me exposed and vulnerable. It gave a kind of physical shape to my own psychic pain. One of these photos became the cover of my first chapbook, Marco Polo, and other ones have gone on to be published in journals and books, though I never sold one of the prints, I think in part because they can be disturbing, though not to me.

The poem itself explores my deepest personal struggle, one I share with so many women. We are still brought up to think that a woman who doesn’t ever experience pregnancy and childbirth is not a really a woman. If we cannot have children, we feel shame and perhaps unworthy of love, and if we chose not to have children, or it just never happens along the way, then we feel guilty, like we are perhaps not whole. This places such tremendous pressure on the woman, and so in the poem I pose the question of why can’t the aberration – the deviation from the norm – be beautiful, be celebrated. And what does it mean to be an aberration, how is the word defined? As it turns out the word has such a wide range of definitions – none of them particularly positive – and yet the definitions themselves are beautiful and poetic and have to do with light, images, seeing, and even the movement of celestial bodies.

This poem was published in Tupelo Quarterly along with two of the mannequin photos which I digitally manipulated to engage further with this poem. Visually, the poem mirrors the crack in the mannequin, which creates a duality that further illustrates my own struggle between two possible selves, the one with children, and the one without. The last line becomes a kind of suture – yes, these issues seem to separate women, but they ultimately draw us together on a deeper level. The poem is also about distortion. The first line is deliberately not capitalized in a kind of rebellion against norms. Everyone who looked at this poem – excepted for the editors who published it – was bothered by that, and at times I was too. But that was exactly the point! As a writer I find it important to always be interrogating ideas of normality as well as language, societal structures, rules and laws. If we are not vigilant, all of them can be used against us.