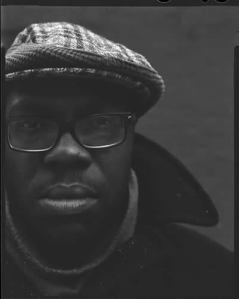

Dr. Huey Copeland is an Associate Professor of Art History at Northwestern University and the author of Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America, published just last year by the University of Chicago Press. On Thursday, March 6th, he will discuss his new book project In the Arms of the Negress: A Brief History of Modern Artistic Practice when he visits EPL’s 1st Floor Community Meeting Room at 7 p.m. as part of the Evanston Northwestern Humanities Lecture Series. While exploring a transnational history of modern contemporary art, Dr. Copeland’s lecture will examine how the figure of the “negress” has influenced the way black women are represented in the visual arts as well as the way they represent themselves. In anticipation of his visit, we recently spoke with him via email about the origins of the term “negress,” the Art Workers’ Coalition vs. MoMA, his forthcoming book, and the pioneering black women artists you should know.

Evanston Public Library: Could you define the term “negress” and discuss its origins?

Huey Copeland: Négresse is a word referring to black women that has been in circulation, at least in Francophone discourse, since the 17th-century. Because of the historical context in which it emerged, the term has, in many ways, been inextricable from a whole host of racist and sexist connotations that black women artists have worked with and against.

EPL: In your excellent essay “In the Wake of the Negress,” you explore how the art of black women is often excluded from museums such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Could you discuss the reasons why? Who are some notable artists absent from MoMA’s collections?

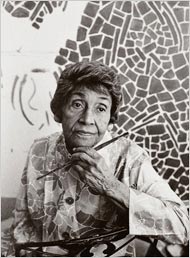

HC: As subjects marked by both race and gender—clear liabilities within Western cultural hierarchies—black women artists have been doubly negated. The Museum of Modern Art has yet to collect the work of pioneering artists such as Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Senga Nengudi, Alma Thomas, or Edmonia Lewis, who will receive special attention in my lecture.

EPL: Your essay also examines how groups such as the Art Workers’ Coalition began fighting in the late 1960s to include more art by black women in MoMA. What were the greatest challenges these groups faced? How successful were their efforts, and how have they continued today?

HC: Black women artists have often had to work on several fronts simultaneously in order to articulate the specific challenges posed by their unique social positioning. While practitioners since the 1960s have been successful in creating more exhibition opportunities for black and female artists as well as in expanding the parameters of aesthetic discourse, much work remains to be done to create a truly feminist and anti-racist art world.

EPL: Who are some artists currently combating the misrepresentation of black women through their work? Do any Chicagoland museums and galleries have strong collections of their art?

HC: “Complicating” and “contesting” are perhaps better words to describe how contemporary artists of various stripes, including Zoe Leonard, Kalup Linzy, Lorraine O’Grady, and Wangechi Mutu—the subject of an upcoming retrospective at Northwestern’s Block Museum of Art—intervene within the visual sphere and so build upon the legacies of giants such as Chicago’s own Margaret Burroughs.

EPL: How is work progressing on your new book In the Arms of the Negress: A Brief History of Modern Artistic Practice? Have you had any big surprises or encountered any unexpected challenges during your research?

HC: Slowly, but steadily! Given the sheer number of representations of black women that populate Western art of the last two centuries, one major hurdle has been deciding what works to focus on and why. Equally challenging has been the attempt to narrate a history of art that is neither hide-bound by strict linear chronology nor reductive in its approach to individual works and practices.

EPL: What do you hope patrons will to take away from your March 6th lecture “In the Arms of the Negress?” Can you suggest additional books or resources for those interested in learning more?

HC: I hope the audience will come away with a more expansive sense of what is possible within artistic practice as well as a critical awareness of how the canons of Western art reflect the social reproduction of white supremacy. My own thinking about these questions has been deeply shaped by Hilton Als’s The Women, T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting’s Black Venus, and the work of black feminist critics such as Michele Wallace, all of which makes for inspiring reading!

Interview by Russell J.