Yesterday I happened to read the editor’s introduction to the latest issue of Orion magazine. Orion is generally considered to be a “nature” magazine, and is usually shelved with similar titles at most newsstands and bookstores. But as the editor points out, Orion never intended to be viewed as any particular genre or fill any specialized niche within the magazine market. From Orion’s point of view, any writing anywhere that anyone is doing is in a sense “nature” writing. Since we all live in the natural world, any writing about people or place is in a way, writing about nature. The introduction describes how the term “nature writing” gained acceptance, and eventually its own section in bookstores, which ended up being somewhat counterproductive to those truly concerned with the subject. When a book or an author became pigeonholed as a “nature book” or a “nature writer,” and got segregated into the proper section of the bookstore, along with them went the possibility that a reader just browsing for good writing would stumble across the books. The “nature” shelf became a destination to be sought out, difficult to find if you didn’t realize you were looking for it. Now, flash-forward to today’s world where “nature” has become “ecology” or “environmentalism” sections in the bookstores and buzzwords like “green” and “eco-” are slapped on books (and innumerable other products, deserving of the adjectives or not) willy-nilly in an effort to create a certain trendy image, and thus enhance sales. But, my cynicism aside, Orion makes the argument that the mainstreaming of the ecology and environmentalism has broken “nature writing” out of its mold, and given writing about the natural world a whole new life and relevance. These books no longer have to be qualified as good books about nature, but can now simply be good books. This is very good news, because as global warming and other challenges make our environmental concerns ever more pressing, it is vital that nature and humanity are recognized as inseparable, two parts of the same living whole. Orion states that:

Literature grounded in the natural world . . . can have a sort of Trojan horse effect, whereby the writing itself earns a place in people’s hearts and, once there, can promote the idea that nature is what makes us human, that what we do to the environment, we do to ourselves. The more people relish this good literature, the more they come to understand the danger we are in ecologically speaking, the better the chances that humanity will rise to meet the challenges that lie ahead.

It was with these thoughts and words running through my mind that today I happened upon a new book by Lewis Blackwell entitled The Life & Love of Trees. Most would consider the book to fall under the aforementioned “nature book” category, since it is, after all, a book about trees. But just having read the Orion essay, the book struck me as so much more than just a book about nature. And the more I explored the book the more I understood Orion’s point that a book about the natural world is a book about all of us, a book about everything.

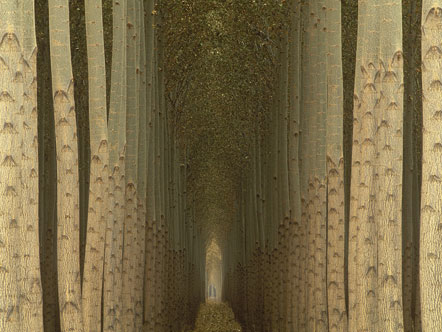

The heart of the book is hundreds of large-scale, full-color photographs of trees taken by nature photographers from around the world. Interspersed with the images are brief yet profound quotes, poems, musings, and aphorisms about trees from all manner of writers, scientists, artists, world leaders, and other wise men and women from throughout history. Reading through the list of names of those quoted is intriguing. It seems everyone from Blake to Churchill, Thoreau to Einstein, Warren Buffett to Helen Keller has had something appreciative to say about trees. I was especially moved by a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “The wonder is that we can see these trees and not wonder more.”

Reading this quote and others from the book started me to wondering about what we think of today when (and if) we think of trees. Living in an urban environment certainly can do strange things to a person’s relation to and sense of nature. There are many days when one never even sees a tree that wasn’t planted intentionally as part of someone’s landscaping scheme (not that there is ever anything wrong with planting a tree, but it gives a different sort of feeling than that of a tree that naturally grew up out of the ground somewhere with no other assistance than what nature allowed for). But even outside of urban areas trees are ever more rapidly being ripped from the ground to make way for “progress,” in any of its myriad guises. Looking around at the man-made structures that we’ve erected in the place of nature’s fine and varied work makes me wonder what we are thinking to allow the world to be so unnaturally and unaesthetically altered in this way. And more to the point, if we are thinking of these things at all. When was the last time you really thought about a tree? When was the last time you appreciated a tree, were glad of its presence as it offered you a cool, shaded place to sit, provided you with its delicious fresh fruit, gave you a foothold to climb up and see the everyday from a different perspective, or simply just shook its bare black winter branches against a cold gray sky and allowed your mind to wander off for awhile away from the awful tedium of daily practicality? If you don’t have an answer but wish you did, perhaps you will find something to inspire you in The Life & Love of Trees.

In addition to the sublime photography and bite-sized profundity, author Blackwell’s accompanying text is personal and engaging, exploring the nature of trees and their various connections to the world and our lives. In the book’s two sections, Life and Love, he examines (in very accessible language) the science and natural wonder of trees, and the more intangible aspects of how trees are able to affect the human soul, identity, and memory. Blackwell and the trees take you around the world and share all manner of remarkable facts and stories about the multitude of varieties of trees which inhabit the Earth. When faced with such an assemblage of awesome (and I mean that in the truest sense of the word: inspiring awe) information, it is difficult to pick just one fact to serve as an illustration. But turning to a page at random, I learn that the largest-girthed tree in the world lives in the Mexican town of Santa Maria del Tule. It has a circumference of 118 feet. More astoundingly, it is around 1,600 years old, and will likely outlive anyone living on Earth today. Think on that for awhile.

The Life & Love of Trees is a beautiful and amazing book. Whether you are inclined to regard it as a nature book or a necessary book is up to you. But regardless, if you are at all concerned about the state of the natural world, if you are given to questioning the mysteries of life on Earth, if you are reeling from a deeply felt, yet only half-realized sense of disconnection from nature, of if, like me, you just enjoy watching as the branches at the top of the impossibly tall tree growing up out of concrete in a tiny recess in the alley out your back window blow lazily in the breeze, you should come find this book. It will make you feel many good things. It will make you wonder.