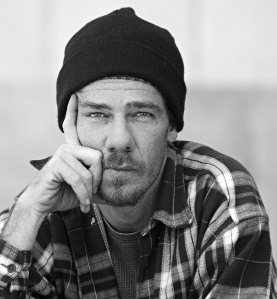

John Sevigny is a photographer, writer, activist, and the latest artist to be featured in our ongoing exhibition series Local Art @ EPL. His show – titled Nomads – is currently on display on the 2nd floor of EPL’s Main Branch where it defiantly dismisses immigration stereotypes in an affectingly intimate photographic series. You can catch Nomads through the end of November, and after that, you can learn more about Mr. Sevigny’s photography and future projects at his website and on his Gone City blog. I recently spoke with Mr. Sevigny via email about Spanish Baroque painting, social justice, innocent male wanderlust, and his forthcoming book El Muerto Pare el Santo.

Can you tell us a little about your background as an artist? How did you get started in art? Was there something specific in your life that sparked a need to create? What drove you to create in the beginning? What drives you now?

Family has a lot to do with it. My father was an artist, and in our house, art, music, religion and politics were the four main topics of conversation and that was true even when I was very small. But more directly, I started taking photographs as art after wandering into a bookstore in Miami – where I was born and raised – and seeing a book by the Spanish Baroque painter Diego Velazquez. There’s a painting called “The Feast of Bacchus”, probably painted in 1629, that hit some nerve in my soul that I didn’t even know existed before. It has something to do with the dark, mysterious, sarcastic realism of the piece. There are some angels and other things in the composition, but what really drew my attention were the faces of these drunk Spaniards. They were obviously real people that Velazquez had seen, and they were hardened, funny, tragic, and everything else that drunks tend to be. Literally from that moment on I knew that if I could tap into the force of that kind of portraiture, I would be able to die happy.

For a long time I was interested in social issues, for example, the way women are treated in the world or the way immigrants live. I’m still interested in those things, but as I get older, I’m increasingly drawn toward something more obtuse, more spiritual, something more universal. But it’s all about the same thing in the end. The social and the spiritual both deal with the human condition. There is something social and spiritual about the portraits of immigrants that are up at the library right now, you just have to look for the spiritual element a little bit harder. But it’s there.

How do you describe your art? Do you see yourself as fitting in with any specific artistic movements or styles? Do you work in other mediums in addition to photography?

How do you describe your art? Do you see yourself as fitting in with any specific artistic movements or styles? Do you work in other mediums in addition to photography?

The three words that I use a lot to describe my photographs are dark, mysterious, and gritty. I also try to make photographs that are beautiful but not in the obvious ways.

One of the things that makes them work – but also causes some confusion – is that my pictures are not easy to classify. This gives them a strength, but also puts me at odds with what I call the Art Industry which seeks to put everything into little boxes so that it can be easily marketed and sold. My work isn’t exactly documentary, but it isn’t just decorative either. It’s not journalism, but it doesn’t really look like most people’s idea of art. This is something that happens, almost inevitably, to artists who work in a very sincere way. Describing their work is like trying to describe a fingerprint because it’s just as singular.

Your biography mentions that you’re “a descendant of a family of Methodist Civil Rights activists” and that your “work frequently addresses issues of social justice.” How has your family influenced your work as an activist? How do your art and activism influence each other? What are the social justice issues about which you feel the most passionate?

Social justice is something that all people, everywhere, are interested in because all of us want to be treated fairly. That said, not all artists choose to allow those kinds of themes to enter into their work. I think I was very naive when I started doing this. I assumed that all artists were interested in the human condition. It took me a long time to learn that a lot of people – particularly in photography – were far more interested in money, fame, attention, or other things. That said, I think that artists who only deal with social issues are very boring – just as boring as people who only paint flowers or only photograph landscapes or only work with nudes.

Getting back to issues themselves, I am very concerned about the treatment of immigrants, not just in the United States, but in Mexico and Europe. It seems to me that people are naturally nomadic and have always moved around to find better fields to harvest, better jobs, more money. To try to regulate the flow of people in and out of a country is one thing. To criminalize it is simply wrong.

Can you describe what first influenced you to create your “Nomads” series? Did you start out with the goal of injecting some humanity into discussions of immigration or were you primarily interested in exploring the idea of “innocent wanderlust” in young men?

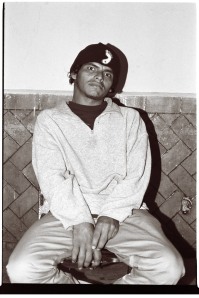

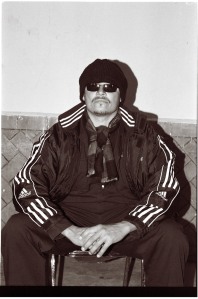

At first I wanted to give human faces to the numbers. We’re bombarded with statistics about everything, and we’re also bombarded with statistics about undocumented immigrants. The innocent wanderlust was something I discovered while working on the pictures. A lot of these young men were just happy to be on the road. If this project had a theme song it might be “Ramblin’ Man” by Hank Williams Sr. It has something to do with immigration as an “issue” but it has a lot to do with the age-old desire of young men to hit the road. There’s a story in there that’s something like Exodus from the Old Testament, but there’s also a story in there that’s more like Twain’s Huckleberry Finn or Kerouac’s On the Road.

Can you tell us more about the young men in “Nomads?” What is your connection with the immigrant shelter in Saltillo, Mexico? How did you come to be introduced to the men, and how did you set up the photographs? Did you interact much with the young men before or after you photographed them?

At the time, I was doing some volunteer work for the Roman Catholic Diocese which operates the shelter which is called Belen Posada del Migrante – one of many church-run shelters for Central American immigrants in Mexico. I do not work for the shelter, but I do work with the director Father Pedro Pantoja quite a bit in organizing art events to help connect the shelter to the community at large.

I met the young men in the photographs, and many, many more, simply by visiting the shelter and talking to them. In some cases they asked me to photograph them. In others I asked them. What I wanted to do was highlight their diversity by putting them in front of the same wall sitting on the same chair so that the only things in the photographs that would change would be the faces and the bodies in them. We had some very wonderful conversations about Central America – a region I love – and the United States, where many of them were headed. We also talked about the things all young men talk about: women, work, food, money, and the rest.

I met the young men in the photographs, and many, many more, simply by visiting the shelter and talking to them. In some cases they asked me to photograph them. In others I asked them. What I wanted to do was highlight their diversity by putting them in front of the same wall sitting on the same chair so that the only things in the photographs that would change would be the faces and the bodies in them. We had some very wonderful conversations about Central America – a region I love – and the United States, where many of them were headed. We also talked about the things all young men talk about: women, work, food, money, and the rest.

Could you describe the choices you made in composing your “Nomads” photographs?

I wanted a diversity of faces, first and foremost, because I wanted the pictures to be educational. Many people don’t know that there are Central Americans who look stereotypically Anglo and others who have what are considered African or Asian facial features. There is an assumption in the States that everyone who “looks” Latino is Mexican which is something that drives Hondurans, Guatemalans, and others absolutely crazy: first, because the word “Latino” encompasses an enormous group of people from indigenous Mexicans to blonde-haired, blue-eyed Argentines of German descent; and second, people generally want to have their nationalities recognized correctly. So the choices were made with those issues in mind.

You stated you began creating your “Nomads” series between October 2008 and January 2009. Do you have any plans to develop the project further?

I would very much like to make more of these portraits. Sadly, I am extremely busy right now self-publishing and self-distributing my first book of photographs which is called El Muerto Pare el Santo. I hope to have more time next year to work on this project and start new ones.

What other future plans do you have as an artist, activist, writer, and teacher? Could you tell us more about your upcoming book, El Muerto Pare el Santo?

Last year was just consumed by exhibitions. I was looking over my calendar recently and realized I’d done 19 solo shows in 12 months – from Oshkosh, Wisconsin to Guatemala City – which must be some kind of a record for an independent artist. It seems like I was on the road constantly in 2010. After the holidays and a few months of talks and book events, I want to pull back a little bit and focus on new photographs. The subject matter will determine itself through working – as it always does for me – but the big goal is to take pictures, and of course, meet new people and have new experiences.

I can’t possibly express how proud I am of the book, El Muerto Pare el Santo, which is my first. It contains 40 photographs which deal with issues of life, death, and existence – which in the end are the only three things that exist. There is no single social theme, but people who know my work will see references to ideas and topics I’ve worked with before from poverty, to exploitation of women, to spirituality and religion. But what the pictures in the book are meant to do is show a richness in the world that transcends any “issue” through landscapes, still lives, and portraits. It is a very strong selection of photographs put together in a very nice way and printed to the highest possible standards. People who have seen it say they’ve never seen anything like it, that it’s a strange and beautiful project.

How do you find Evanston and the Chicagoland area as a place to work and exhibit as an artist? What inspires you as an artist about the community where you live?

I have always liked Chicago. I first visited the city when I was a kid and have always felt that people here have what I’d call a healthy disinterest in whatever is happening in New York or Los Angeles. There’s a very brave and admirable attitude of “we don’t care how you do it in other places.”

Saltillo, Mexico is not on many people’s lists of places to visit, but I find it unusually fascinating. It’s a medium-sized city high in the desert, and it sits in a sort of shallow bowl formed by mountains so you can see the whole place from anywhere you’re standing. It’s a conservative city, and like so many other places these days, we’re cursed with inept political leaders. But we are blessed with a small, strong community of artists, poets, thinkers, journalists, and religious leaders whose mindset goes far beyond the confines of the community.

Interview by Russell J.